Oregon Art Beat

Painter Lindsey Holcomb, contemporary Native American artist Rick Bartow, metal artist Kelly Phipps

Season 27 Episode 2 | 28m 28sVideo has Closed Captions

Oregon artists Lindsey Holcomb, Rick Bartow and Kelly Phipps.

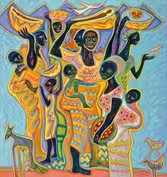

After her MS diagnosis, Lindsey Holcomb began painting MRIs — first her own, then 400 others around the world — turning pain into beauty. Rick Bartow (Wiyot) is considered one of the most prominent leaders in contemporary Native American art, best known for his emotional, expressive drawings, paintings and sculptures. His art is held in over 100 museums and public collections across the country.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Oregon Art Beat is a local public television program presented by OPB

Oregon Art Beat

Painter Lindsey Holcomb, contemporary Native American artist Rick Bartow, metal artist Kelly Phipps

Season 27 Episode 2 | 28m 28sVideo has Closed Captions

After her MS diagnosis, Lindsey Holcomb began painting MRIs — first her own, then 400 others around the world — turning pain into beauty. Rick Bartow (Wiyot) is considered one of the most prominent leaders in contemporary Native American art, best known for his emotional, expressive drawings, paintings and sculptures. His art is held in over 100 museums and public collections across the country.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Oregon Art Beat

Oregon Art Beat is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipMore from This Collection

Oregon Art Beat is excited to share our extensive archive of Oregon artist’s as content-rich support for educators. In this painting collection, meet painters en plein air and in the studio working on canvas, on plywood and on the sides of buildings. They draw from current events and their own histories discovering some surprising techniques learned through experimentation and practice.

Calligraphy artist Sora Shodo, Oregon Zoo X-rays, Rock Poster artist Justin Hampton

Video has Closed Captions

Japanese calligraphy artist Sora Shodo, Oregon Zoo x-rays, rock poster artist Justin Hampton (25m 45s)

Bhavani Krishnan, plein air painting | K-12

Video has Closed Captions

Bhavani Krishnan picked up a paint brush, igniting a long-forgotten passion. (8m 26s)

William Hernandez, colorful and surreal | K-12

Video has Closed Captions

William Hernandez paints wild colorful scenes highlighting the surprising and the surreal. (6m 3s)

Paula Bullwinkel, photography to painting | grades 6-12

Video has Closed Captions

Paula Bullwinkel's paintings summon a nostalgia that's as familiar as it is unsettling. (9m 26s)

John Simpkins, painting in solitude | K-12

Video has Closed Captions

Painter John Simpkins draws inspiration from the open spaces of eastern Oregon. (8m 41s)

Betty LaDuke, painting and activism | K-12

Video has Closed Captions

Betty LaDuke is a Southern Oregon painter. (9m 51s)

Alex Chiu, muralist | grades 6-12

Video has Closed Captions

Alex Chiu is a Portland-based cartoonist and muralist. (3m 1s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for Oregon Art Beat is provided by Jordan Schnitzer and the Harold & Arlene Schnitzer Care Foundation Endowed Fund for Excellence... and OPB members and viewers like you.

Funding for arts and culture coverage is provided by... [ ♪♪♪ ] [ ♪♪♪ ] LINDSEY: Multiple sclerosis has shaped how I create, why I create.

When I first saw my MRI in that neurology office, I'll never forget it.

It was, um, a fearful moment.

Later, I painted an abstract interpretation of my MRI.

When I finished it, I felt a lot better and I felt like I could maybe digest things a little bit more the next day.

[ ♪♪♪ ] And it was something that I shared on my social media.

The National MS Society shared it on their channels, and it catapulted me into art.

I've just painted my 399th brain.

I've worked with people in almost every US state and about 14 countries.

Hey!

WOMAN: Hi!

Good to see you.

Yeah, have a seat.

Sorry, there's Pyrenees hair.

It's okay.

[ both laughing ] Is this your most recent image?

It is the most recent.

What are you hoping to see color-wise?

I love gold and emerald, purple, teal, pink.

When I have my MRIs, because I'm claustrophobic and they put that helmet on your head, that's just terrifying, so while I go in, I imagine that there's an octopus wrapped around my head, comforting me, and that has helped me with my anxiety.

So you can have fun with that shape... Love that so much.

...if you want.

STEPHANIE: It was hard, because my dad was also diagnosed with MS, and he passed away when he was 59.

So to get the diagnosis, it was scary, it was terrifying.

The fact that I'm given a chance to turn this terrible disease into something beautiful, to give some sort of a power back to myself, um, there's a lot of emotions with that.

[ ♪♪♪ ] LINDSEY: Alcohol ink, there's a lot that's a surprise.

This is the making of octopus tentacles.

What I've just done here is cut out the lesions that are highlighted on Stephanie's MRI with a wood-burning pen, and what I do next is probably my favorite part.

I'll line them in this gold ink.

It's the nod to kintsugi, which is a process in Japan that repairs a broken ceramic vessel with gold lining, the crack, basically highlighting the vessel's history and celebrating it, versus trying to hide it or tossing the entire vessel away.

It feels like applying a balm to what we worry about most, which are the lesions showing up in our MRI.

My grandma was a seamstress.

I have put her thread on almost every single one of my artworks.

That's kind of my way of honoring her.

In addition to the MRI paintings being very heavy, heady emotionally, there's a lot of details that I recognize now are not going to be something that I'm going to be able to do indefinitely.

I do get a lot of joint stiffness, fatigue, cognitive fog.

Spasticity affects my fine-motor ability.

MS can affect my vision in a way where it's almost like I'm looking through a torn tissue paper.

There's occasionally double vision.

I've challenged myself to create with my eyes closed.

I just kind of have to be at peace with whatever I'm able to do on the day that I wake up on.

Where I'm at in 2025, I'd say that I space out the amount of MRI paintings that I do.

[ ♪♪♪ ] I started a natural ink series this last summer.

This is a lot easier to work on.

Less detail.

And it's something that I can see well on a good vision day, on a bad vision day, and it's turned into something that has been fun with my children, where they're telling me what shapes they're finding.

And up there, there's an eye.

And then over there, I see, like, a smiley face with one eye kind of thing.

LINDSEY: It felt triumphant to be able to do these really smooth, large shapes.

Before MS, I come from an administration and events background, and so, you know, it kind of is your role to take on everybody else's stress.

My joy is much better and bigger pursuing a more creative path.

[ turn signal indicator clicking ] [ soft jazz playing over car stereo ] When people get my artwork, I think my favorite thing that has been shared is that waiting for it kind of feels like a holiday morning or a birthday.

Because they're excited to see their MRI, and we do not get that moment as a patient.

Hi.

[ chuckles ] STEPHANIE: Hi.

I've got a painting for you!

[ clicks tongue ] [ Lindsey hums ] Oh, wow!

[ Lindsey laughs ] Oh, wow.

New MRI.

[ voice breaking ] It's... It's phenomenal.

[ Lindsey sighs ] I love it.

I see the octopus.

Mm-hmm.

Oh, wow.

I love the octopus so much.

[ laughs ] I had so much fun with that.

Lindsey, this is stunning.

[ sniffles ] I feel like I'm not alone.

Um... [ sniffles ] It's just another step in my healing, a very, very beautiful step, so I'm... obviously overwhelmed with gratitude and emotion, so... I think I need a hug here.

[both laugh ] Yes, hug!

I'm, like, lost for words.

Oh, my gosh!

Of course.

It was my pleasure.

Oh, my gosh.

It's amazing.

Hey, guys!

Hi.

Welcome home.

How was school today?

It was good.

It was good?

Hey, you.

[ ♪♪♪ ] LINDSEY: MS really refocused what is most important to me, and that is having energy for my young, growing family and for things that feed my soul.

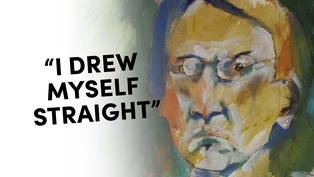

This is "Things You Know But Cannot Explain" by Rick Bartow.

He created it in 1979, and you can see the elements that would go on to define his work: the emotion, the raw, aggressive style, the eraser marks, the darkness.

Flash-forward, and he would be known for pieces like this... and this.

He even had an installation in the garden of the White House.

Bartow went from a small-town Oregon kid to having his work in the collections of over 100 museums across the country.

He's not just a big deal in Northwest art but American art as a whole.

But all of this almost didn't happen.

Bartow was born in Newport, Oregon, in 1946.

His father was from the Mad River Band of the Wiyot Indians in Northern California.

His mother was white.

He started making art early in life, encouraged by his aunt.

Bartow graduated college with a degree in art education.

But that same year, he was drafted into the Vietnam War, where he served as a teletype operator and a musician in military hospitals.

He saw the horrors of the Vietnam War firsthand, and it disturbed him deeply.

RICK: I received a Bronze Star basically, I think, for playing guitar in the hospitals on my time off.

The only thing heroic that I know I ever did was play music for people who were sick and dying, in horrible pain.

Bartow came home in 1971, suffering from what we now call PTSD.

He felt guilty for surviving when so many others didn't.

He lost nearly a decade to alcohol and drug addiction.

But in the early '70s, he met an elder with the nearby Siletz Tribe who taught him traditional practices like the sweat lodge and helped him reconnect with the natural world.

And Bartow kept making art all the time.

RICK: I could only afford graphite at the time, and that made a black drawing on a white sheet of paper.

But in the end, what a wonderful spiritual, uh, sort of symbol, you know, light and dark, you know?

It's the dance, you know?

Over time, he's dealing with mortality and death and grieving.

Sometimes they are self-portraits where you see a skull behind him or you see the skull within him.

This became Bartow's path.

RICK: Yeah, plain and simple.

I drew myself straight.

Not only from PTSD stuff but also from alcoholism.

KATHLEEN: I do think there is a raw emotional quality to his work, especially his works on paper.

When you see the marks that he makes, it is almost as if he was attacking the surface of the paper.

He didn't seem like he planned his work.

It really feels very spontaneous.

If there was something he didn't like, he would cross it out.

RICK: I can spiral all around.

I can do anything I want because it's my drawing.

But I really like these eyes, the way they were working.

There's something going on there.

[ ♪♪♪ ] He was not shy about expressing things about himself that, you know, might be considered dark or ugly.

He was just being who he was, and that was a complex person who dealt with a lot of tragedy and probably made some decisions that he regretted and wasn't afraid to show that to the world through his work.

In some pieces, Bartow erased almost as much as he drew.

Hmm.

He said, "I use erasure because my life has been shaped as much by what I have lost as by what I have gained."

Bartow lost his father when he was 5.

He witnessed countless deaths in Vietnam.

His first wife died 12 years into their marriage.

He recorded these losses and his own transformations in an ongoing series of self-portraits.

[ ♪♪♪ ] KATHLEEN: "Artist Upset Self" is a very good example of one of his self-portraits.

You can recognize him immediately from the glasses he's wearing and the shape of his nose.

He is frowning, and his face is kind of emerging from a dark background.

But in other cases, I think that he is using animal imagery to express some part of himself.

There's one work on paper in particular called "Alpha My Anger," and it is a dog, and it's kind of viciously snarling at the viewer.

I see that as a self-portrait as well.

He really identified with the character of Coyote, who is a trickster figure in a lot of Native American stories.

You know, you sometimes see these animals transforming back and forth from human to beast.

RICK: Well, then it begins that blending where people get caught saying, "Oh, are you a shamanic artist?"

No, I'm just an artist who thinks that people and animals share the same bed.

And if the bed isn't comfortable for them, it's not going to be comfortable for us very long.

I think he was a magnificent sculptor.

"Dog Pack" is a collection of three dog sculptures.

They have kind of this gnarly look to them, but when you look up close, you think maybe they're not so bad, maybe they're just street dogs that might be misunderstood.

He really had a gift for creating these animals that almost seem like they could be alive.

He definitely was influenced by other Native American artists and Native American art traditions.

But he was influenced by many artists in the Western canon as well.

Artists like Frances Bacon, Cy Twombly, Richard Diebenkorn.

KATHLEEN: I think you can see influences by Goya specifically in his work.

There is even a painting that references Goya by name.

As his work progressed, his paintings and drawings grew larger, more colorful.

In 1997, his carving "The Cedar Mill Pole" was installed at the White House.

He followed that up in 2012 with a piece called "We Were Always Here," now a permanent installation in Washington, D.C.

[ ♪♪♪ ] In 2013, he suffered a major stroke, forcing him to relearn how to speak and how to paint.

KATHLEEN: So "Sing Crow" was a painting that was done not long after this experience.

There's a figure that's hunched over, it's not really a comfortable work to look at.

I don't think that his health problems ever kept him from continuing to express himself through art.

Being able to continue to make work as long as he could, to almost the end of his life, was quite important.

Bartow's health issues continued, and in 2016, he died of congestive heart failure.

Since that time, his stature in the art world has only increased.

Major museums continue to acquire his work every year.

In 2024, San Francisco's de Young Museum acquired "The Magical Mind in Rural America."

18 feet wide and 6 feet tall, it's the largest piece Bartow ever created.

I do think that he felt like he was leaving a mark and leaving evidence of who he was, and I don't know if he was really thinking about the far future and how his work would be viewed by so many other people.

I almost think that, for someone like Rick, his success might've even been somewhat of a surprise.

I feel like his work was so introspective for so long that he was really making it for himself.

RICK: Suddenly I realized the Creator had given me something to do.

And whether people understood that now didn't matter.

I have to do this.

This is my job.

If I don't want to, I can turn my back and it'll go someplace else, you know?

You'll do it or you'll do it or you'll do it.

Somebody else will do it.

But if I want to, here's my gift and I can use it today.

[ ♪♪♪ ] KELLY: I like to go to salvage yards, any kind of store that carries lots of old junk and tools.

Here we go.

Yeah, check it out.

She's a beauty.

Primarily I look for shovels, wheelbarrows, toolboxes, anything I think that would be interesting to cut out.

[ gasps ] Score!

Score!

After doing this for 17 years, I just know what I like and what catches my eye.

There's no rhyme or reason to my madness.

[ laughs ] I draw everything freehand just straight onto the metal.

My designs are just something that comes out of my head.

I really like detail and I like to draw really small, intricate things.

[ ♪♪♪ ] The tool I use for cutting my metal is a plasma cutter.

Plasma cutter is pressurized by oxygen.

Oxygen runs through a very small channel, and inside that channel is an electrode.

And when you fire that plasma cutter, it heats it up to about approximately 30,000 degrees Fahrenheit.

And so when I'm using the plasma cutter, it's basically like I'm drawing with fire.

There is some danger when doing plasma cutting.

I have had injuries.

Slag goes down my boot, gets stuck in my sock.

You know, by the time you get your shoe off and stuff, it's burnt.

I got some good scars.

Okay.

I think I like working with metal because it's got endless possibilities of what you can do with it.

I like the idea of taking a hard, static metal and turning it into something soft and beautiful.

[ ♪♪♪ ] Besides the shovels, I create anything that looks fun to cut out: Old toolboxes, wheelbarrows, I do a lot of signs... gates, fences, you name it and I will make it.

[ laughs ] [ ♪♪♪ ] [ laughing ] [ ♪♪♪ ] I was invited onto the rat rod team last year by my friend Gary Fisher, who builds rat rods and asked me if I'd be interested in doing some artwork for it.

A rat rod is blended pieces of art from all different kinds of cars: motorcycle parts, plane parts, Ford Chevy, blended to make one beautiful piece of art.

My reason for bringing Kelly on was to... bring something totally new that hasn't been created before into a culture that is blue collar all the way.

There's nobody else like her.

There's nobody else that could do her work, and I knew that I had to up the game.

I've never been around that scene of building a car from scratch.

[ ♪♪♪ ] [ engine rumbling ] I just felt flattered, and I felt so good to be a part of the team.

It was so fun.

I know all the great builders, and they knew when she put that piece together, it stepped up the whole game of rat-rodding and the culture.

June of last year, we took the car to St.

Louis for the competition, and it was quite a spectacle.

There's 500 cars that show up there, and it's just like this mega free-for-all of rat rods.

The judges are looking for creativity, uh, just something that's totally different.

It was down to the final 12, and they were starting to eliminate the different vehicles.

KELLY: It got down to, you know, like three left, and then two, and we were... you know, it could go either way.

The moment they announced the winner, it was screaming and yelling and pictures and a big trophy.

It was really fun.

I have a new project in the works.

It's a 1936 Chevy pickup.

Okay, so I want to hang this to see what it's going to look like.

Is it suicide door?

Want to go on that side and I'll open it up for you?

It opens like that.

That looks pretty cool.

I like that.

Suicide it is.

KELLY: I'm kind of starting to sketch on it in different places on the truck, ideas that I have for cutting it out.

I want quite a bit of art on it.

I would like to be one of the first women to build a rat rod and enter it in a competition.

I think that would be super cool.

I'm very excited about doing this project.

It's time-consuming and it's-- It's a-- I'm learning a lot, so that's a great thing for me.

It's a good challenge.

Climb in.

[ laughs ] Yeah.

Yeah, I like it.

Perfect.

[ ♪♪♪ ] To see more stories about Oregon artists, visit our website... And for a look at the stories we're working on right now, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.

[ laughing ] Support for Oregon Art Beat is provided by Jordan Schnitzer and the Harold & Arlene Schnitzer Care Foundation Endowed Fund for Excellence... and OPB members and viewers like you.

Funding for arts and culture coverage is provided by...

This Oregon artist became an icon through intuition, classical training and Native wisdom

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S27 Ep2 | 10m 25s | Rick Bartow went from a small town Oregon kid to having his art work in over 100 museums. (10m 25s)

Turning MRIs into artwork: How an Oregon artist, Lindsey Holcomb, transforms pain into beauty.

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S27 Ep2 | 9m 13s | Transforming MRIs into artwork, Lindsey Holcomb is helping people cope with multiple sclerosis. (9m 13s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Oregon Art Beat is a local public television program presented by OPB